Text © World of Showjumping

A horse stomach is a complex organ with different anatomic regions. Nevertheless, there is a tendency to generalise stomach problems and any gastric diseases are often referred to as a ‘gastric ulcer syndrome’. World of Showjumping had a chat with equine veterinarian Jaak Van Overstraeten* to understand why a wide view is needed when looking at the horses’ gastric health.

“The common term ‘gastric ulcer syndrome’ is more like an umbrella expression which covers different diseases – each with varying causes, prevention and treatment,” Jaak begins. “People tend to do as they are used to; they look at gastric ulceration as one disease and consider omeprazole as the only treatment. However, to make it simple: A sore head can be caused by a migraine or a tumour – and you don’t treat them both with aspirin. Often, horses are looked at only from an orthopaedic view.”

“For the moment, the only way to truly know what is going on in the stomach is to do a gastroscopy,” Jaak continues. “I don’t know an orthopaedic vet who does not take x-rays – and no one complains about that. However, I often have to do a lot of convincing to get a gastroscopy done. Clinical symptoms can be very different: Some horses can have severe gastric lesions with no symptoms, and we see horses with almost no gastric lesions and a lot of symptoms. Not all horses with gastric problems are skinny, or aren’t eating well or have coat issues: These certainly are normal symptoms, but there can be more. We see many horses who clinically look normal but have severe ulceration and therefore perform under their usual level.”

“Clinical symptoms can vary from developing colic to stereotypical behaviour,” Jaak continues. “It is a question of which was first: Is the horse behaving in a certain way because it has stomach ulcers or is the behaviour causing the ulcers? Problems in performance can be connected to gastric issues and even though there can be many aspects affecting the horses, the stomach certainly plays a role in the bigger picture.”

To understand the difference between the many gastric issues, it is essential to know the basic anatomy of the stomach, Jaak explains. “The stomach of a horse is a relatively small, contracting organ: It is only about 10% of the whole digestive system, and can hold approximately 20 litres of content at a time,” Jaak says. “The superficial part of the stomach is called squamous, and the deeper part – in the direction of the small intestine – is the glandular part. It is important to remember that, normally, there must be a continuous outflow from the stomach to the small intestine: If horses go long periods without food, there can be reflux of bile acid in the stomach which can cause problems. Therefore, it is essential to feed regularly, and not in too big portions at the time. It is also important to keep in mind that if horses are treated, it can cause changes in the acidity of the stomach – which in its turn has an effect on the rest of the digestive tract.”

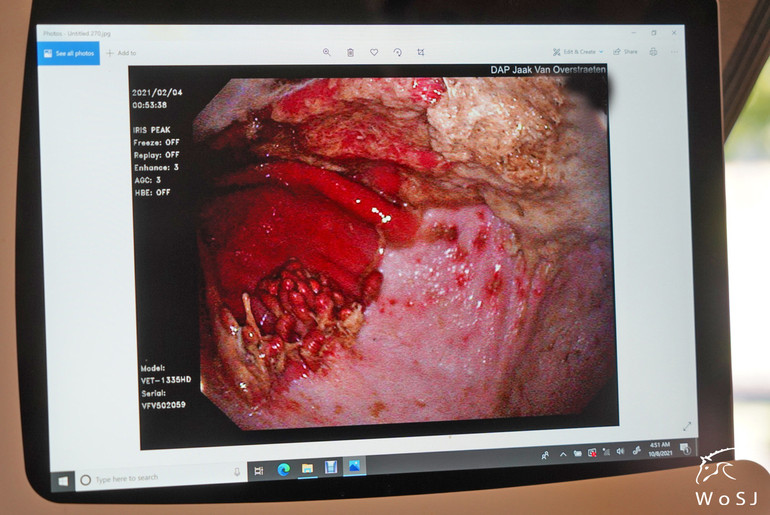

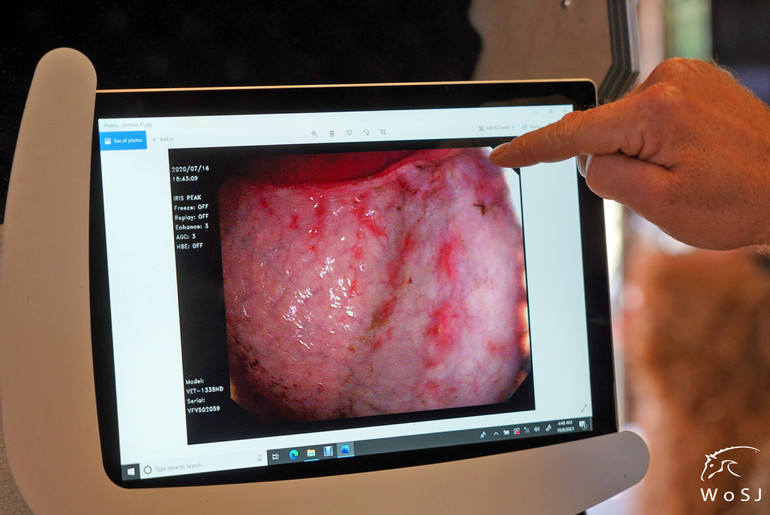

Two of the most common issues in the stomach are the equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD) and the equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD). “The equine squamous gastric disease means the horse has ulcers located in the superficial part of the stomach,” Jaak says. “This part of the stomach is not made to have contact with acids. Therefore, whenever acids splash to this part, it burns and causes lesions. In the equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD), the ulcers are located further down in the lower part of the stomach, where the issues are created due to the integrity of the barrier which protects the mucosa.”

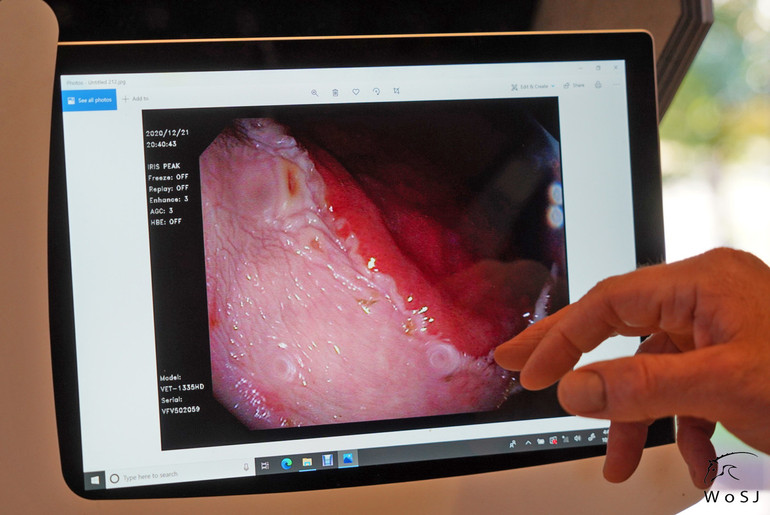

"This picture shows the margo plicatus, the separation between the glandular (red) part and the squamous part of the stomach, the grandular part is hyperemic, the lining of the margo plicatus is irregular and there is mild ulceration of the squamous part (grade II and III), there is also fibrin visible on the squamous mucosa which is caused by old lesion," Jaak explains. Photo © Nanna Nieminen for World of Showjumping.

The treatment for these two diseases varies greatly. “Horses suffering from ESGD can be helped with omeprazole, and changes in diet can help enormously, whereas horses with EGGD tend to respond poorly on omeprazole alone, while the combination of omeprazole with sucralfate has better results. There are many differences between the two diseases and that is the key point everyone should know. For example, stress factors play an important role in the glandular disease but much less in the squamous,” Jaak points out.

In general, a healthy stomach begins with the right diet, Jaak points out. “The base diet of a horse must be good hay in necessary volumes – for a normal warmblood horse you would need approximately 10 kg per day,” Jaak says. “Secondly, we should supplement with grains but as little as possible. Feeding intervals play a bigger role than what you feed: In nature horses look for food all day. There are also benefits in feeding hay before grains: Horses will be calmer and will eat slower. When the stomach is filled with hay before grains, the outflow of grain will be slower and the risk of developing colic due to too much sugar in the hind gut will be lower. Also, feeding hay before work is important and we have a lot of evidence supporting this: Hay has an enormous buffering capacity, and it absorbs the acid in the stomach, leaving no free liquid in the stomach. The upper part of the stomach – squamous – is not made to have contact with the acid. Think of running with a bucket of water – where the water is acid – and the water splashes. If you fill the bucket with hay, the water is absorbed and will splash less. When your horse starts working – not in walk, but in trot and canter – you have an enormous abdominal pressure caused by the musculature of the abdomen which pushes towards the stomach and mixes the content. When the acid makes contact with the upper part of the stomach, it causes ulceration.”

“The intensity of work plays a huge role,” Jaak continues. “In general, horses with squamous gastric problems are better when worked not too long: The longer the work takes, the longer the acid is in contact with the mucosa, causing more lesions. Work often but not too long – walk is always ok but trot and canter not longer than 15-20 minutes at a time. Also, consider implementing two to three rest days per week, certainly for horses diagnosed with EGGD. Some stress factors, such as transport, are hard to manage as many horses are used for competition and they have to travel. There is not much we can do than to look for the best environment. In general, being educated and adapting the small details usually already helps.”

While omeprazole is often considered as the first aid for any gastric issue, Jaak advices to be cautious. “When necessary, I think horses should be treated with omeprazole. However, I believe treating them because we think they have ulcerations is not a good idea,” Jaak explains. “For example, combined use of phenylbutazone and omeprazole – even though it is common practice – is not a good idea. Last year, a study on the impact of concurrent treatment with omeprazole on phenylbutazone-induced equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) was started at the Louisiana State University, but it had to be stopped because of two fatalities and severe lesions. Researchers think this can be caused by microbiome changes, changes in intestinal motortype and intestinal inflammation. Therefore, the combined use of these two forms of medication can actually cause more harm than good – contrary to what many seem to believe.”

“In human medicine, omeprazole seems to play a role in the calcium metabolism and we now see that people when treated with omeprazole in their younger years, are more prone to developing bone fractures – which in sport horses is something that should not be overlooked,” Jaak continues. “However, the duration of the treatment is more important than the dosage: Better results have been found in horses treated even with little dosage over a longer period versus a big amount in short periods. When giving omeprazole, the diet of the horse should also be considered. Generally, studies have shown best results when the horses treated with omeprazole were not given hay during the night and were given their medication 30 minutes prior to feeding.”

"Thanks to researchers such as Professor Ben Sykes we already know a lot about the equine stomach, but for the future there is still a lot of research to be done when it comes to fully understanding the stomach and its importance," Jaak says. "Equine microbiome in the colon is one of the hot topics in the equine internal medicine at the moment and will be for the next years. In human medicine it is already proven to have an enormous effect; changes in the microbiome play a role in the development of diseases like Alzheimer and many things that at first sight might not seem to have a connection. All these things can be even more essential in horses as they have a much more important hindgut than humans: they need to digest the grass and have a bigger microbiome flora in the large intestine.”

* Jaak Van Overstraeten graduated Magna Cum Laude from Ghent University in 2000. He first worked in general practise before founding his own private equine practise with special interest in internal medicine and reproduction. Jaak specializes in referral work from colleagues in the field of internal medicine.

No reproduction without written permission, copyright © World of Showjumping.com