Text © World of Showjumping

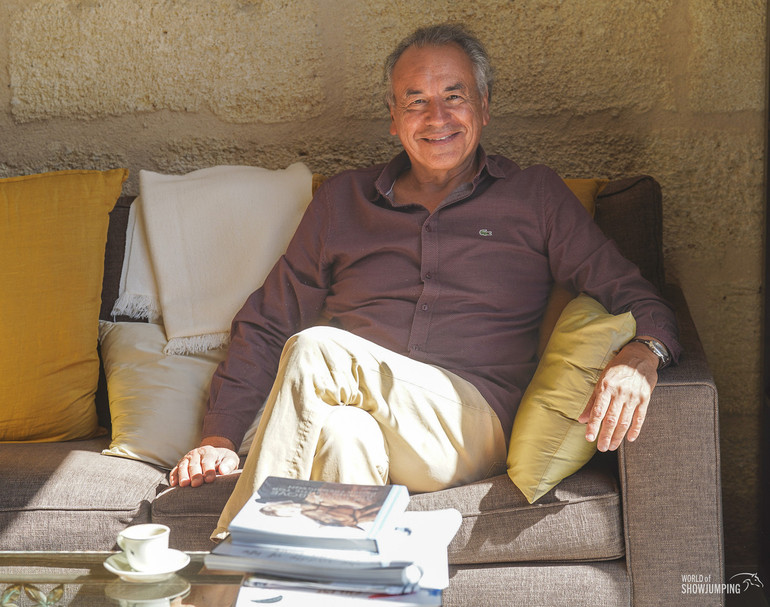

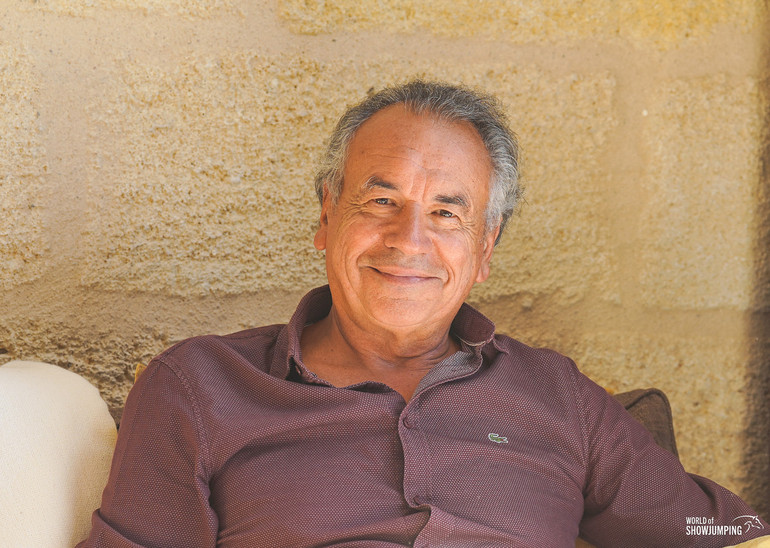

“The best part of my life was when I competed,” Pierre Durand – 1988 Olympic Champion – tells World of Showjumping. With his legendary Jappeloup (Tyrol II x Oural), Durand took part at four Europeans, two World Championships, two Olympic Games and five World Cup Finals, becoming European Champion in St. Gallen in 1987, Olympic Champion in Seoul in 1988, and team World Champion in Stockholm in 1990 – all while simultaneously working as a lawyer. For a decade, the iconic French duo captured hearts wherever they went.

To World of Showjumping, 68-year-old Durand tells the story of Jappeloup – a love story, though not at first sight. However, there is more to Durand than his exceptional horse and their deep relationship. “I took my own way,” Durand says as he looks back at his career. “I didn’t do all that I have done for the eyes of others – for the public – I did it all for myself. I did what I dreamed of, and with that, I am happy. Do I miss it? Of course. Competing on the high level is so emotional, it is like a drug. You push yourself to your limits, and when you don’t have that kind of challenge in your life anymore, it gets boring – naturally.”

Captivated by coincidence

With a father who was president of the soccer team in his village, Durand grew up surrounded by a strong appreciation for sports, though not equestrian – no one in his family rode. “It was by accident that I fell in love with horses,” he recalls. “I used to go biking with my grandfather around our village, and one day we passed a horse in a field – and I was totally captivated. It was the first time I was so close to a horse, and I was fascinated, impressed, completely in love.”

After this initial meeting at the age of ten, Durand asked his parents if he could start riding. However, it was not easy, because there were no riding schools close by and he ended up starting with a whole different discipline – eventing, which in the south-west of France, where Durand grew up and still lives, was more popular than showjumping. “After a bad fall, my mother did not want me to continue riding,” he recalls. “However, my father was a diplomatic man and convinced my mother to allow another discipline; showjumping, where the fences were not fixed and thus not so dangerous. I was thirteen at the time, and that was the beginning of my story with showjumping.”

Not a fulltime professional

Durand studied law, and after university he worked as a lawyer – parallel to his riding career. “Most riders at the time were professionals, like Nick Skelton, John Whitaker, Ludger Beerbaum, Franke Sloothaak, Ian Millar, Eric Navet,” Durand recalls. “I was really in a particular situation, but it was my choice. However, I was very professional in my methods with my horses. I had a small stable, never more than five horses, because I had no time for more and wanted to really pay attention to the horses I had.”

After being a part of the French national team as a junior, Laudanum was Durand’s first good horse and until today, many top horses carry the stallion’s blood. “He was a thoroughbred, not tall – only 1.62m – and I won my first big Grand Prix with him in Pau. I was twenty and him, only eight,” Durand recalls. “It was an international show and many famous English, Spanish and French riders participated in this Grand Prix. Next to Laudanum, I had another thoroughbred called Carrefour, and I won a lot of speed classes with him. I had these two thoroughbred horses that were good for the highest level; Laudanum for the Nations Cups and Grand Prix classes and Carrefour for the speed classes.”

And then, Jappeloup came into Durand’s life.

Jappeloup

What came to be a legendary partnership, was not a love story from the very beginning. In fact, it took a lot of convincing from Henry Delage – Jappeloup’s breeder – and Durand’s father before the two would even meet. “Jappeloup’s father Tyrol II was a French trotter and his mother Venerable was a thoroughbred – it was a crazy mix for showjumping,” Durand tells. “Jappeloup’s breeder lived close to me, and when I was junior, he was always nice to me: When I had success, he would congratulate me, tell me how he believed in me and that he was quite sure that one day, he would have a horse for me. And sure enough, one day, he did.”

Jappeloup was four when Delage – totally convinced of his exceptional talent – first brought the little black horse to Durand’s stable. “He was a little horse – 1.58m, not more. When I first saw Jappeloup, I thought ‘well, Mr. Delage is a nice man, but he must be crazy – it will be impossible to jump on the highest level with his horse’,” Durand tells about his first impression of the horse that came to change his life. “However, it was really difficult for me to tell him how I felt, because he was such a nice man. Therefore, I made up an excuse of being busy with my studies, of Jappeloup not being fully grown, and asked him to come back in a year – with the hope of him forgetting by then.”

However, Delage took Durand’s words to heart, and whenever the two would meet at shows, he would update Durand on Jappeloup’s improvement. “I tried to get away from seeing the horse again, and Mr. Delage picked up on how uninterested I was,” Durand tells. “He was close with my father, and many times around the dinner table, my father would tell me that I was not being nice to this man who wanted to give me his horse. In return, I would ask my father if he had ever seen this horse; it was impossible! However, my father told me he had in fact seen the horse and seen it jump, and that it had been incredible. My father said he thought Jappeloup was certainly no normal horse.”

Durand’s father and Mr. Delage organized another meeting for Pierre and Jappeloup – but the horse looked exactly the same as the year before. “He was still 1.58m, and in front of the saddle he was a thoroughbred, while behind he was a trotter,” Durand explains. “However, I agreed to keep him for one month. The breeder was so happy, but for one month, I did not ride Jappeloup. The day before calling the breeder, I thought to myself that I was not a nice man if I didn’t try this horse at least once. So, I decided to take him for a hack in the forest, just for a walk. I was alone with him inside the forest, and he spooked at every little thing, a leaf, or a bird – but with such energy. He had atomic energy, something I had never felt before. I came back from our walk, only convinced that he was a strange horse. Throughout the evening, I kept thinking what I should do; keep him or not. And, the next day, as I called the breeder, he didn’t let me speak and said straight away, ‘hello Pierre, so you are calling to tell me that you are keeping Jappeloup?’ And without deciding beforehand, I simply agreed – and he never left my stable.”

Truly special

Later on, Jappeloup showed Durand the exceptional quality he had. “First of all, he was careful – naturally careful – because he was afraid of the fences,” Durand tells. “In addition, he had this atomic energy about him, and he was strong in his body – maybe thanks to the French trotter blood as they are strong horses. He was never lame, and never sick. Jappeloup had many qualities to be an exceptionally good jumper, but it was difficult for me to see all that in him in the beginning; it was impossible for me to imagine how he could be. I started to believe in him when we won our first French title. He was seven and we fought against the best French horses and riders at the time, and we were the only pair to jump clear in all five rounds. Flawless over five rounds, at only seven years old! This was when I first thought he could be successful at the highest level.”

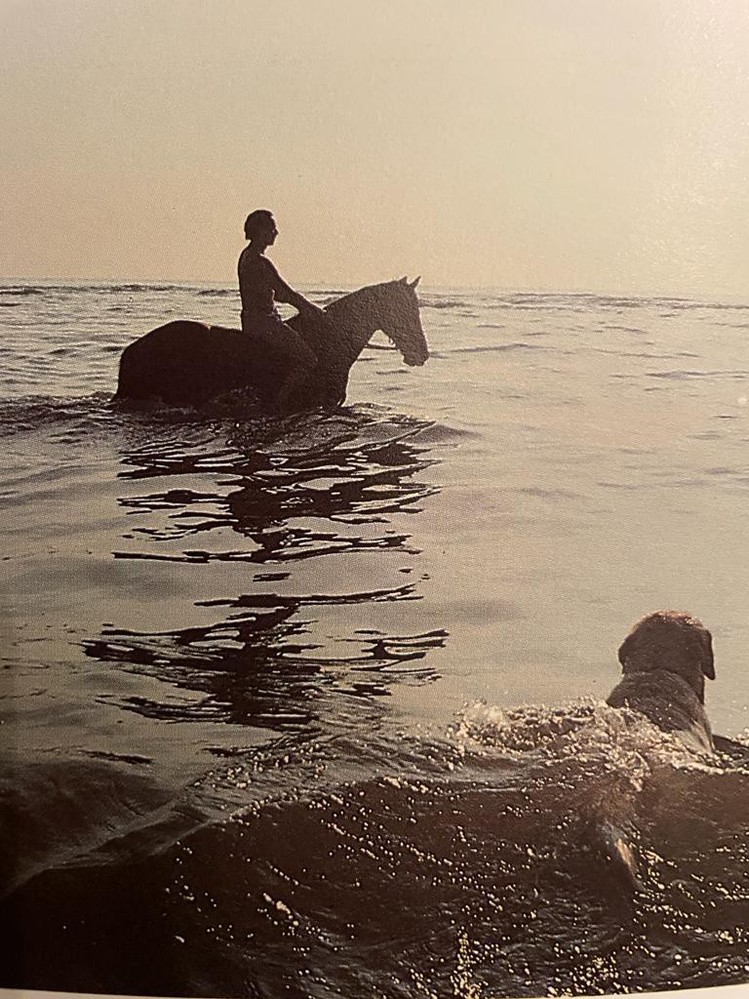

As a personality, Jappeloup was independent and strong on his own, Durand tells. “However, he was very sensitive and emotional as well; he was afraid of many things. He had a big heart, was nice with people – he was simply special. Jappeloup had a pure style on the jump, and I worked him a lot on the flat, he was nice to ride and had a good level of dressage. Basically, he could have competed in dressage as well; he knew everything.”

When Jappeloup was 16 going 17 – and after over a decade of competing together on the highest level – Durand decided it was time to retire him from the sport. “I was very happy with this decision because he was really fit; shortly before we had been 5th in the Grand Prix of Calgary as well as 3rd in the Grand Prix of Rotterdam. He was really in good shape, and I felt happy to stop when he was at the top of his career and in good health. However, shortly after – in November 1991 – he died of a heart attack in his box at home. I was destroyed, because I was looking forward to having him around, just spending time with him and riding him in the forest. On the other hand, he died young, and he didn’t suffer. However, it was really, really hard for me to lose my friend.”

One year after Jappeloup’s sudden passing, Durand stopped competing. With his mare Narcotique, he was going to be a part of the French team at the 1992 Olympic Games. However, two months before the Games, the mare was lame and the two were unable to compete in Barcelona. “I had decided to stop competing at the end of the year 1992,” Durand tells. “It was enough for me.”

Still competitive today

Even though the sport has changed, Durand believes that Jappeloup would still be competitive today. “It would be difficult to be better than he was, but I think today’s courses would probably suit him even better than those in the past,” he says. “Back then, the courses and fences were very big, and the oxers were wide – larger than today. Jappeloup was able to jump under any circumstances, and his strength was especially in between the fences; I could do what I wanted with the distances, add or leave out strides. Today, the courses are technical, the fences are lighter and as he was really careful, I think he would still be competitive. He was like a cat, he turned really short, and today – in general – the arenas are smaller.”

Jappeloup’s story has by now been adapted to a movie. “It is a beautiful movie, but it is not my story,” Durand says. “I don’t recognize myself in it, I don’t recognize my father, and I find that Jappeloup is not acknowledged as the star he was. I am disappointed and sad when I think that young people might get the idea of me not being nice to my horses. It is not my personality, not my character; I was close to my horses, I had a deep friendship with them. The character in the movie is spoiled, without time for his horses and for riding – I was not like this. I am sad because the movie would be more educational if it was correct: It would be educational to show the exceptional relationship I had with Jappeloup, the connection between a rider and a horse that is needed to be the best. You don’t see this special bond with my horse in the movie, which is a pity. As the next generation watches the movie, the message should be that if you want your horse to give you the best of his heart, you have to be fair with him, you have to love and understand him and be close to him.”

On being different

Looking back on Durand’s career, it is not only his exceptional horse and the fact that he never rode full-time that made him stand out from the rest – he also had a very different approach to the sport in general. “I worked a lot on the mental aspect of the sport and at that time, nobody spoke about this,” he tells. “However, I understood very early that at the high level and in true competition – at the biggest championships, like the Olympic Games – it was the mental aspect that made the difference.”

“Back then, it was hard to speak about this part of my preparation, because the others – professional riders – thought that I was a crazy man to need psychological support,” Durand continues. “However, I was not crazy, I simply wanted to be in control of my emotions and ready when it was really important. I am quite sure that it made the difference for me. I saw many good riders – riders better than me – losing a great part of their power at the most important moments. They lost their head, and they lost the title. Riding is not just a question of the technical side and of having a good horse, in the very end the results come down to the mental state of the rider. I didn’t have a coach for riding, but I had a mental coach; I believed it was more important. When it came to riding, I would speak a lot with the other riders, I would watch them and I simply tried different things on my own. I did not have a teacher, but I had chef d’equipes in the French team and of course within the team we would discuss technical issues and speak about our sport, but I never had a coach – except a mental one.”

“I know that today, many riders include the mental side to their training and many riders work on this. In my time, it was not usual and sometimes it was difficult to speak about it because many would laugh at me, saying they didn’t need it – they were strong enough. But in my opinion, no one is strong enough. When your career depends on two minutes – because two rounds at the Olympics is two minutes, not more – you have to be ready. If not, it is finished, and you never get a chance to get back to that moment that mattered. I think the attitude is different now, and in the French team they have included mental preparation as part of the program. However, I am sure some riders are still not convinced.”

Another difference to Durand was the fact that he understood he had to own the horses he rode, in order to be free. “I am very independent and I like to be that way, not to depend on anyone,” he explains. “I wanted to choose the competitions I did, without anyone telling me what to do. And I understood from the beginning that in order to be independent, I had to own the horses I rode myself – or at least half. This was necessary, in order to have no stress, to be free, to decide by myself, and not be explaining why I had one down. And I know this world – our world – is not always a nice one. When you rode good horses at my time, other riders would go around to the owners and tell them maybe they would be better. I was always at least a part-owner in all my horses, and with Jappeloup I was the sole owner – 100%, luckily.”

Shared emotions

Even though Durand stopped competing in 1992, he never stopped riding and still gets on a horse every now and then. “What I enjoy the most in our sport is simply being with the horse,” he says. “I love to work them on flat, to improve their schooling and the connection. I don’t like to ride a horse as you would use a car; I like to create a strong connection, I like to know my horse, I want to improve our relationship. I am very happy when I see that a horse understands what I ask of him and improves – that is the best feeling.”

“In the past, my first motivation was to be Olympic Champion. It was my dream and my main goal, and I followed this goal all along my sport career. I also had a strong motivation for the big championships, because all the others are trying to be the best as well, and you have to win against a field that is really focused and peaking on that occasion. I like this true moment of sport; it was my motivation to be the best at these moments.”

Durand’s fondest memories from his career include his European title in St. Gallen, the team gold in Stockholm, and naturally, the individual gold in Seoul. “There are many, many good memories,” he says. “My European title in St. Gallen maybe means the most to me, because I think it is harder to become a European Champion than an Olympic Champion. The Europeans go over four days, with five courses, the difficulty is high and you have to be very consistent. The format is still the same as it was in my time. That year, it was a real fight against John Whitaker and Milton. Luckily, I won the Table C on the first day and John was second, but until the end, he was right behind me. It was a really challenging battle, where Nick Skelton came third. The competition between us was tight, and, at the time, John and Milton were usually the best. Jappeloup and Milton, black against the white, during four days – it was really, really great sport. For me, it is my best sport memory. My most emotional memory is when we were crowned World Champions in Stockholm with the French team. With a team the pleasure is always stronger, because you share it. And, of course, Seoul, because it was my dream to be an Olympic Champion – it was a great moment.”

The most difficult moment of Durand’s career was in Los Angeles in 1984, where he fell off in the second round of the team competition. “In between Los Angeles and Seoul, I worked a lot on my mind, and it was funny because in Seoul four years later, I was in the exact same situation as in Los Angeles,” he tells. “Again, I was the anchor for the French team, it was the second and deciding round, and there was the necessity of being clear if we wanted to be on the podium. It was a special situation and when I went inside the ring, I remembered the situation four years prior. However, this time I was stronger, and I was really happy to be clear. As we were standing on the podium with the French team, I felt at peace; I had managed to do what I failed at four years prior.”

Money and power

Durand has stayed very much involved in the sport after his successful career, following the changes closely – and he is concerned about how parts of the sport are evolving. “Today, the financial power is too important,” he begins. “If you want to be on top, you have to compete in a closed five-star circuit where many pay to participate. Except the small group of riders at the very top of the ranking, an organizer will not choose you for your sport results but for your ability to pay. The worst part is that this is the reality not only on five-star level, but at four, three, and even two-star level too! You have to pay to compete, pay for a table… the first criteria is not your talent, not your result, it is money that comes first. For me, this is a form of discrimination, as in sport, the first criteria should always be the sport– being the best, having the results – not just having a lot of money. This change I have seen in our sport is sad, and I am afraid that one day, equestrian sports will be out of the Olympic Games due to this financial discrimination. I don’t want to be old fashioned; I understand that the world we live in today is what it is, but I don’t like what I am seeing. I worry for our sport; perhaps one day we realize we have lost sport in what we do and are left with only a show.”

“Before, it was a little bit different,” Durand continues. “In my time, the FEI was run by Prince Philipp who was followed by Princess Anne. They were aristocratic, and money was not a question for them; the sport was truly at the centre of the politics of the FEI,” Durand says.

A change of mentality is needed

Horse welfare is another point of concern for Durand. “It will maybe be the most important question for the years to come, because there are strong political movements for the welfare of animals in general,” he points out. “If we as a community are not able to change our mentality and adapt our rules, I am really afraid that one day there will be a huge scandal. An example of this is what happened in Tokyo with the modern pentathlon, which we should see as a major warning sign. The IOC does not want a sport ridden with problems, what they want is to give a modern face for the Olympic Games. They want to include new modern sports, which are more attractive for a young population. Today, the IOC’s problem lays in their relationship with the young people, who are not very interested in the Olympics. However, because the IOC wants to limit participation to 10500 athletes, choosing a new sport means that an old discipline has to go. And ours is a traditional sport, it is expensive to organize, there are questions with the welfare of horses – I am afraid that our sport has too many problems for the IOC.”

Durand believes that the equestrian community is not fully aware of the severity of the current situation and does not understand the importance of being accepted as a sport by the wider society; the social license to operate. “Our community is really small and happy to be as they are, not caring about the outside world. The mentality has to change completely, from the FEI to the riders, who in my opinion are not so separate. In the end, it is too often about the same interest – money – for all stakeholders in our sport. Sadly, it is less and less about the horse and the sport, and more about money and power. Money is a good servant but a bad master.”

Not enough solidarity

After freely dedicating eighteen years of his life to the sport following his riding career – first as the president of the French Equestrian Federation and then as the president of INSEP, the National Institute of Sport, Expertise, and Performance in France – Durand ran for FEI presidency in 2014 in an attempt to give back to the sport that has given so much to him. Nearly a decade later, Durand reflects on his goals from the time of his candidacy and what he would have focused on had the result of the election been different. “I would have done my all to keep the sport as a priority,” he says. “You cannot be totally against the financial evolution, but as an example, I think the CSIO events where the riders are selected by their national federations should be rewarded with more ranking points than the closed circuits – you cannot compare them. To keep a fair balance, where the sport comes first and is the first criteria in everything, would have been my aim. Also, I would have kept the old formula with four riders and a drop score at the Olympic Games.”

“I am all for horse welfare, and I would have limited the amount of shows horses can compete at,” he continues. “I think that the horses are competing too much and they should be protected more than they are today. The FEI speaks about the welfare of the horses, but in my opinion, it is mostly marketing communication – an official position that should have more real substance behind.”

In Durand’s view, the current FEI voting system makes it nearly impossible for any real opposing influence. “It is really difficult to have any influence with the voting system they have in place, with the small nations with no real equestrian activity having the same vote as the big nations like Germany or France,” he points out. “Riders need to be stronger and more united. When I was a candidate in 2014, I had no real support from the riders, and then after, they met me and said ‘oh it is a pity you were not elected’.”

“I feel too old to fight again, especially without support – you need the riders in your back, and financial resources too,” Durand concludes. “I ran for the FEI presidency to serve my sport again – both horses and riders - in a positive way. However, I have seen how the political kitchen cooks and I don’t want to do that again. I want to be in peace, in quiet – I want to stay free.”

5.10.2023 No reproduction of any of the content in this article will be accepted without a written permission, all rights reserved © World of Showjumping.com. If copyright violations occur, a penalty fee will apply.